Minggu, 23 Januari 2011

English Cat Sh*t One Promo Video Streamed

Culturomics?

Could social scientists and humanities scholars be replaced by bots?

From the December 17, 2010, issue of the journal Science comes a News of the Week piece “Google Opens Books to New Cultural Studies.” It sketches the ongoing research of a mathematician, Erez Lieberman Aiden, who is studying word frequencies using all of Google Books as his data source. Here’s the abstract of the technical publication.

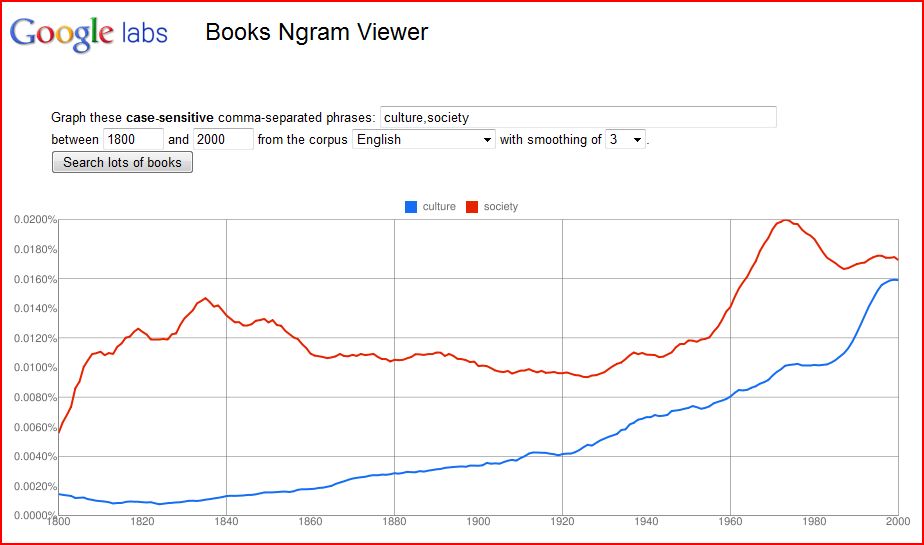

By analyzing the growth, change, and decline of published words over the centuries, the mathematician argued, it should be possible to rigorously study the evolution of culture on a grand scale.

…

The researchers have revealed 500,000 English words missed by all dictionaries, tracked the rise and fall of ideologies and famous people, and, perhaps most provocatively, identified possible cases of political suppression unknown to historians. “The ambition is enormous,” says Nicholas Dames, a literary scholar at Columbia University.”

Just what the humanities needs! More studies of domination and resistance.

I already tend to view quantitative research with a skeptical eye, although I appreciate the insight statistics can provide when they’re well done. However this project immediately rubs me the wrong way and its not just the fawning praise of its massiveness. (Quantitative research, motto: “Size Matters”)

Why are word frequencies significant? The whole thing seems like a glorified version of those inane word count “studies” done by Ok Cupid like this one on gays and straights or this one on whites and non-whites.

To understand a word’s meaning (as opposed to its definition) you have to look at context, style, and tone. In short you have to read to interpret. Which is why I was particularly intrigued by how the researchers and their collaborators at Google navigated the copyright controversy associated with the Google Books project.

The project almost didn’t get off the ground because of the legal uncertainty surrounding Google Books. Most of its content is protected by copyright, and the entire project is currently under attack by a class action lawsuit from book publishers and authors. [Peter Norvig, head of research at Google] admits he had concerns about the legality of sharing the digital books, which cannot be distributed without compensating the authors. But Liberman Aiden had an idea. By converting the text of the scanned books into a single, massive “n-gram” database – a map of the context and frequency of words in history – scholars could do quantitative research on the tomes without actually reading them.

Take that hermeneutics! Now we can interpret texts without reading them.

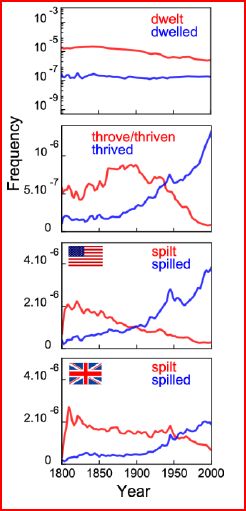

I’ll allow that there is a significance to word frequencies. After all stuff like this (from the online supplement to the technical report) is pretty cool:

Why it matters, I’m not so sure. But it is kinda neat.

Leiberman Aiden is a student of genomics by training, so by naming his new study “culturomincs” he’s playing a little word game. Genomics is a very broad field of study that features as its principle methodology using math and statistical modeling to draw conclusions about gene frequency within a population. For instance, genomics might inform clinal studies showing how gene frequencies vary geographically among humans. Culturomics seems to apply this idea through analogy, taking words for genes and language for the genome.

But there are limitations to how far this analogy can go. There is no part of the genome that is beyond the purview of genomics, but culturomics, with its data set limited to scanned pages of Google Books does not consider “culture” in its entirety. Admittedly Google Books is great in scope, “It currently includes 2 trillion words from 15 million books, about 12% of every book in every language published since the Gutenberg Bible in 1450.” But even to intentionally limit the study to language and set aside all non-linguistic aspects of culture, you are still bound only to the written word. And the published written word at that.

More importantly genetics, of which genomics is but a subfield, is only one of many different perspectives for understanding an organism or population. You are not your genes. There is much, much more that goes into making a living organism what it is than just its genetic composition. As the father of identical twin girls I can testify to this. Although each sister’s DNA is a perfect copy of the other’s they are very different people. Genomics helps geneticists draw conclusions about gene frequencies, it does not tell us which genes are turned on and off or how genes interact with their environment.

Culturomics, by analogy, doesn’t come close to its grand claim to be a rigorous study of the evolution of culture. It can provide us with some interesting information about word frequency, however. The question is, what are you going to use this new tool for?

“This is a wake-up call to the humanities that there is a new style of research that can complement the traditional styles,” says Jon Orwant, a computer scientist and director of digital humanities initiatives at Google.

…

Humanities scholars are reacting with a mix of excitment and frustration. If the available tools can be expanded beyond word frequency, “it could become extremely useful,” says Geoffrey Nunberg, a linguist at the University of California at Berkeley. “But calling it ‘culturomics’ is arrogant.” Nunberg dismisses most of the study’s analyses as “almost embarrassingly crude.”

Perhaps a problem lies in how the culturomic search has been limited to only variation in word use over time, when there are so many other variables to be considered. In the results above, showing that “spilt” became less popular as “spilled” became more dominant, one is left wondering… So what? That’s an interesting description of language and the documentary function is valuable, but what good is it? How can such descriptions inform what we know about the way humans use language to interact with one another?

What questions would you ask of culturomics? You can run your own culturomic experiments here.

Award Winning Anthropological Writing

I just went through the “Section Prizes” page of the AAA website and listed all the award winning books and articles listed there. I limited myself to works published after 2008 which I could find references to online. That means I included books listed in Amazon.com which only received “honorable mentions,” but did not list award winning student essays for which no online link was given. Unfortunately a lot of the links on the AAA site were dead, and many AAA sections don’t properly list their award winners, or haven’t updated their pages since 2007. The list is also missing award winning English language works from other anthropology associations outside the US. I’d love to add such works to the list as well if someone can point me to such lists. Or if you have a Mendeley account, you can add them yourself.

Since I haven’t yet read any of the linked works, I won’t comment on what the list tells us about the state of our discipline, but I imagine a thorough investigation of the listed works might be able to tell us something – especially if we were able to compare it with a similar list from a decade ago. I did notice that about half of the listed ethnographies are available on Amazon Kindle for about $15 which encourages me to think that I might actually read some of them!

Without further ado, here is the list.

Reflections on Haiti…

It has been one year since a 7.0 magnitude earthquake decimated Haiti on January 12, 2010. In the weeks after the original tremors, many if not all of us read, watched, and listened to reports of the aftershocks—seismic and social—that turned Haiti into one of the worst disasters on record. On the anniversary of that tragic event, the SM team invited new contributors Heather Horst, Erin Taylor, Chelsey Kivland, and Laura Wagner to reflect on their time in Haiti and reactions to the earthquake. The responses ranged from the first-hand accounts to meditations on structural challenges. Over the course of the day, we will be posting these contributions.

On Community and Inequality in the Haitian Earthquake

[This is a guest post by Chelsey L. Kivland, and is part of our series Reflections on Haiti. Chelsey is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at the University of Chicago.]

January 12, 2010 was a beautiful day. It had been the fourth day in a series of such beautiful days, sunny but not too hot with a cool breeze that gained strength in the evenings, ensuring a set of restful nights. Early that morning, I left the house I shared with a friend and fellow anthropologist and a Haitian couple in the middle-class neighborhood of Lalue, and made my way to Bel Air, an impoverished neighborhood in the center of Port-au-Prince. I had been visiting Bel Air for some four years now to study why their concentration of Carnival performance associations, known as bann a pye (literally, “bands on foot”), had gotten so involved in community politics. Since 2004, they had been attempting to transform their associations into recognized civic organizations in order to stake claims on the multiple agencies that performance governance in Haiti, from governmental ministries to NGOs. They characterized their demands for funds for their performances and for the various social projects they executed in the community as a means of holding those who govern accountable to the standards of respect and equality they sought in and by democracy. That morning I was headed to Bel Air because a group of ti bann, “small bands,” was holding a meeting in order to strategize a plan to get the mayor’s office to recognize them as real bands. This was the first of two such meetings I had scheduled that day, and the only one I would finish.

I was awaiting the second one when, at 4:53 PM, the earth started to shake. I was in the best of possible places—in an open courtyard with only the bright sky and some clouds overhead. I was seated at a round table in the back of an old, wooden, French colonial house that had been converted into the mayor’s cultural offices and an outdoor restaurant and performance space that hosted weekend concerts. Claude, the representative of the Federation of Bann a Pye, and I were awaiting the start of a planning session of the Carnival Committee. Unlike other days, when the committee met around a wooden table inside the house, everyone gathered outside today. From the looks of it, people just wanted to take advantage of the soft sunlight with a cool beer at the bar. Agreeing, the committee chair soon told us that we’d just meet outside today. But we did not hurry to gather the tables together. Claude and I continued to debate about whether or not the mayor’s office would be able to verify that the bands had actually performed the past Sunday, their first scheduled performance of the year. He was telling me how the office hadn’t followed through on their plan to send scouts to check on the bands when a train, or so I had first thought, passed under my feet. Within seconds, I locked eyes with Claude. As the vibrations intensified, voices began to fill the air: “Tremblement de Terre,” Earthquake! Earthquake!

Within seconds of the first trembles, Claude corrected my instincts, honed by a Midwest childhood of tornado drills. He grabbed me from heading toward the patio—whose awning would soon collapse on a young man’s leg—and pulled me into the courtyard. The sharp waves of earth jerked me to the ground and my glasses from my head. I landed before a palm tree. For the next twenty seconds I tried, in terrified silence, to hold the ground with both hands and settle it as though it were a hysterical child. I don’t remember the moment the earth did settle. But I recall Claude telling me to get up. I found my glasses; and then the urgency overwhelmed me. The awning left the man with a shinbone popped through his skin. He had started to cry. His “Amwe,” Help! Help! meshed with those echoing in the street beyond the courtyard’s padlocked steel barricade. A suffocating smell of gas spread from the propane vendor next door. And there was no way to get out.

Two men picked up rocks from the stone floor of the courtyard and began to pound against the padlock that secured the door of the yard’s steel barricade. The man with the broken leg was now bleeding profusely. I ran up to him and told him that we’d find help once we got to the street. We all covered our mouths to ward off the smell of gas, and yelled to those in the street not to light up a cigarette. I believed at this point that it was only here where things shook, and that the barrier would open to reveal the street as it had always been. And I don’t think I was alone in this thought. Once the padlock broke open, the crowd of men pushed each other through the narrow entrance as though we were fleeing a fire. But the street brought no solace. It too was gone.

I remember the huddles of young women from a nearby professional school covered in dust and blood, and screaming about the others still inside the collapsed school building; and the woman who held a dead teenage girl whose head was smashed. There was also a woman with a sheet around her naked body, having fled from a shower. She exposed her nakedness to rip off a piece of the cloth so we could make a tourniquet for the man with the broken leg. We did, knowing he would lose this leg, and then sat next to him, listening to his cries. For each motorcycle that passed I asked the driver to take the bleeding man to the hospital. But their faces seemed to say that each was going to check on wives, kids, mothers, siblings, cousins, friends, houses, and so on. Then Félix, the mototaxi driver, who worked on the corner where I lived, rode by us. Each morning Félix and I exchanged the same banter; he asking me to take a ride and I retorting, “I don’t want to die today; maybe tomorrow, but today I got too much to do.” I thought of the oddness of this joke, as my desire to live now frightened me. Félix took the man on the back of his moto. I had no idea where he was heading. But with them out of sight, I began to head home, dragging my feet down this tiny side street filled with loss, terrified of what lay beyond.

When I reached Lalue, the first cross street and the road to my house, I stopped. It was then that I realized—with buildings tilted, cracked, and in piles of rubble; streams of people covered in soot running frantically; and a long line of stopped cars filled with panicked faces—the magnitude of what had happened. I started to run up the hill, falling once over a concrete block.

The first thing I saw as I rounded the corner to my house was the blood-filled shirt of the woman who lived above me. She was running toward me to tell me that my roommate was still under our collapsed house. After a half hour or so (an hour and a half after the quake), our neighbors managed to free her from the rubble of our house. They laid her on her back in the middle of the street in front of the second floor of our house, which had fallen intact to the ground, sinking the first floor into the foundation like a jack in the box. We all spent that night staring into space, listening to the cries of a woman whose son was buried beneath the house across the street, and a man who had lost three of his brothers and two of his children in the house next to hers.

***

At this moment, I had no idea that Bel Air would see more damage than much of the city, or that fourteen of the people I had come to call friends were dead, including a man and his girlfriend who insisted on throwing me a going away party when I made a short trip to the States earlier that year. I had told him I’d be back in no time, but he claimed, like a good anthropologist, that you can’t leave without the proper ritual—a rooftop party with a bottle of rum, a cake, and a stereo hooked up to a live wire dangling overhead, blasting a steady stream of djazz and rap kreyòl that got me dancing and forty people amused. I had no idea that this rooftop had caved in that day, crushing him, his girlfriend, and members of their families as they watched, in a tiny room below, the loop of music videos that they had been watching that day, like all days.

But my ignorance was not for the reasons that kept my family and friends abroad from knowing that I was alive—the fall of all three cellular carriers’ signals. I did not need to call. I could walk there. But I was too scared to leave to check on them. Scared of stepping out alone; and scared of what I’d find. What I did know was that, if they had survived, they would not have access to the kinds of provisions that we would find where I lived, in this middle class area where people were always prepared to spend a few days inside—prepared, that is, for dezòd (meaning disorder but also, and above all, violence)—as they had done, in 2008, when food riots broke out, or before the quake, when students were protesting the shuttered medical school. These were the kinds of everyday inequalities that I had learned to navigate as a white, foreigner researcher and they now paralyzed me.

When I finally made it to the U.S. Embassy two days later, after my landlord had hunted down enough gas to get us there, such inequalities met me in sharp relief. With IDs buried beneath rubble, our white skin got us through the barricades that would keep so many Haitian Americans out. I was there because my roommate needed to see a doctor. We were to go back to the city. But by the time she was done, and told that despite her shockingly bruised body, she was not to be “medivaced,” our ride had already left. I believe this was my landlord’s way of telling us to go home, home to where home was. We took the advice and stayed. For two days I translated documents for Haitian parents or relatives who would be transporting children to their country of citizenship—the country where they, the parents or relatives of these children, could not stay. And then, a coastguard plane with these children, their escorts, and pregnant Haitian American women flew us to Santo Domingo, and a day later a Jet Blue flight, filled with tourists who, at their resorts in the Dominican Republic, did not feel but a tremble.

It was not until seven months later that I would visit Bel Air, and see that it was hit harder than I ever could have surmised from the reports, in the news or from friends, of its destruction. I was there to attend a meeting of the Federation of Bann a Pye, for they were planning a festival to commemorate the earthquake and to showcase the songs of Carnival 2010 that never saw the crowds. When I arrived with a cake and some rum, the director of the federation handed me two folders of photos and notes that they had collected for me when they heard my house had collapsed and had thought I had lost my notes. Enclosed were the photos I had given them as gifts and some they had taken; drawings of their bands’ flags; lists of band members; transcriptions of songs; and invitations to performances, press conferences, and protests. They said they had heard from my friend and research assistant that another friend had gone to my house and recovered most of my fieldnotes and my computer from my desk (which had miraculously sunk into the foundation with only minor scratches), but they wanted me to have these things anyway. One of the bandleaders took me aside after the meeting ended and told me that he has a lot of respect for me because he knows that I came here to do something, and that, as he said, “You will do what you have for you to do” (w ap fè sa ou gen pou ou fè). A call for accountability and respect, meant to motivate the continuation of that which they do and that which I do, after all.

Mobiles, Money and Mobility in Haiti

[This is a guest post by Heather Horst and Erin B. Taylor, and is part of our series Reflections on Haiti. Heather is an Associate Project Scientist at the University of California, Irvine. Erin is a Lecturer at the University of Sydney Department of Anthropology. For more on their collaborative efforts, click here.]

Just over a year ago on January 7th, 2010, Erin Taylor (see www.erinbtaylor.com) and I received notification that our proposed project on money, migration and mobile phones on the border of Haiti and the Dominican Republic (link) had been officially funded by Bill Maurer’s Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion. Excited by the prospect of conducting new research, Erin and I exchanged emails and set a date to begin to plan what we anticipated would be a small, one-year project that explored the movement of people, currencies and mobile phone signals across the border (and by the same company, Digicel, who radically transformed the Jamaican telecommunications market in the first half of the decade). Five days later, on January 12, 2010, the 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti.

Within days of the earthquake I received an email from an administrator at UC Irvine asking if we still planned to go to Haiti. Since our start date was still a few months away, we saw no reason to cancel our project but recognized that it would likely take on new dimensions as the daily life of Haitians – even in the distant region we planned to work – were transformed by the event and its aftermath. As distant observers, it was impossible not to pay attention to the reports of aid sitting and waiting transport, the use of mobile phones to ‘text’ donations and the non-stop stories circulating via mainstream media, twitter and a range of other social media. Money, mobile phones and (im)mobility seemed to be front and center. A few months later (with additional support from IMTFI), we decided to team up with Espelencia Baptiste (Kalamazoo College), an anthropologist who was spending her sabbatical outside of Port-au-Prince, to begin to look more systematically at what was happening on the ground.

In August 2010, our reconfigured research team began a rapid round of interviews and discussions in different parts of Haiti. Our modest aim was to begin mapping Haitian monetary ecologies in the post-earthquake, with an eye towards the challenges facing Haitians as they sought to access and circulate money. Collectively, we began to learn amazing things about the ways in which money IS moving – just how long (and how much money) it takes to deposit $US 20 into a bank account, the importance of sea routes for moving money from distant locales to Port-au-Prince, the same unit of measurement Sidney Mintz wrote about in the 1960s being used in contemporary markets, the emergence of mobile vendors selling increments of airtime and a range of other practices. While not a shock for most anthropologists, the very fact that social networks and intermediaries are still key to economic practices represents a cautionary tale for entities looking to introduce technological solutions to social and economic problems. They remain central not only because of uneven and unreliable access to banks, computers, mobile phones and transportation, but also because sharing resources is essential to managing the chronic poverty experienced by the majority of Haitians. These connections have become all the more essential.

Our report, a collaborative effort written on Google docs and enabled by Skype conversations while we were spread across the globe (Australia, Haiti and the US), was finalized in December 2010 and has been made available online by IMTFI. The report provides a qualitative snapshot of Haitian monetary ecologies six months after the earthquake, focusing upon the challenges that many Haitians face in their efforts to send, receive, exchange and store money, and the role of mobile phones and other conduits in this process. Specifically, we address three key challenges that shape everyday Haitians’ attitudes towards money, trade and exchange and the potential for social change through new financial services: bureaucracy and Power, time and cost, and security. The report concludes by providing a series of recommendations concerning the importance of social networks and intermediaries in moving money, the incorporation of the Haitian diaspora into financial inclusion models and the broader need to address Haitian values concerning savings, time and forms of exchange.

Something to Laugh About: A Few Thoughts on Humor in Post-Earthquake Haiti

[This is a guest post by Laura Wagner, and is part of our series Reflections on Haiti. Laura is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.]

“Humor is one of the fugitive forms of insubordination.”

– Donna Goldstein, Laughter Out of Place

It is January 12 again. This week is making everything feel raw again. What’s an anniversary, really? Why should the 365-day cycle back to a calendar date, an orbit around the sun, have anything to do with anything? But then, January 12 — douz janvye — like 9/11 for Americans, has become a symbol in its own right. The date is more than just the anniversary of the quake. Douz janvye 2011 means that the international community’s eyes are on Haiti again. Journalists and camera crews are back and asking “How is Haiti doing, a year after the quake?” And the strange thing is, it might be the one week when no one wants to answer that question, when people just want to have the space to remember or to avoid their ghosts.

Today there will be stories about the ongoing failure of international aid, the undisbursed promised donor funds, the decay and absence of the Haitian state. There will be stories about dreadful conditions in the camps. There will be the predictable half-hearted attempts at writing something with a positive spin – a few tired human interest stories premised on “hope” and “resilience.” I want to write something different. I’m supposed to write about the anniversary, but I want to write about jokes.

Haitians are very funny. (How’s that for anthropological nuance?) They like to tease. They like jokes—silly, raunchy, or political. The observation that hardship and humor go hand-in-hand is hardly novel or original; it borders on cliché. Yet humor is something that doesn’t come through in most mainstream media and humanitarian depictions of Haiti, which largely focus on those details of life that are deemed most immediate and newsworthy: the earthquake; the spread of cholera; the ongoing plight of people living in the camps, coping with loss and deprivation and faced with eviction; unfolding political upheaval. All those things are important to know and to act upon, to be sad and enraged about. At the same time, collectively these kinds of news have a flattening effect, rendering individual Haitians exemplary victims who can represent the majority of victimized Haitians, but erasing the kinds of details that make them recognizable, relatable and…human.

So this douz janvye – to remind myself and anyone who reads this that people who died were once simply people, and people who survived are still simply people – I am going about it sideways, writing not about the earthquake or any of the other calamities directly, but rather about the jokes people tell.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The first earthquake joke I heard goes like this:

Jesus and Satan run into each other on the street. Satan says to Jesus, “Look at that country there, Haiti. That’s mine. All the evil, the violence, the suffering – Haiti is my country.” Jesus looks at Satan and says, “Oh, really? Let’s see about that.” Then he picks up Haiti and begins to shake it and shake it, and everyone cries out, “Oh, Jezi, Jezi, sove m Jezi! Save me, Jesus!” Jesus puts Haiti down, turns to Satan and says, “You see? Haiti is mine.”

While Haitians find this joke hilarious (doubled-over laughing, gasping for breath), foreigners never do. I tried telling it to my mother, who found it, in her words, “creepy.” This joke shows the country wedged in a game of one-upmanship between cosmic “good” and “evil,” although the role of the “good” seems awfully tenuous. This humor is dark, absurd, and context-specific – but everyone gets it.

Another earthquake-related joke features traditional Haitian folk characters, dimwitted Bouki and clever, tricky Ti Malis:

Bouki and Ti Malis are looking up at the stars. Bouki says, “Look at all those stars, Malis. Look how many they are, how far away, how they glitter. What do you think it all means?” Malis responds, “Monchè, it means someone has stolen our tarp!”

These familiar characters, whose stories people have heard since childhood, are transposed, like everyone else, to the transformed post-earthquake landscape of tents, camps, and tarps. Yet their predictable personalities – Bouki’s dreamy naïveté and Malis’s cruel pragmatism, key elements of the humor – remain intact and familiar.

People’s personal earthquake narratives – stories of fear, survival and loss – are laced with a surprising quantity of humor. Many people, even those who were injured or lost their homes and loved ones, start laughing when they describe seeing their neighbors who happened to be bathing at 4:53 on January 12 and who fled their homes toutouni, stark naked. And they laugh when I describe how, the first time I pulled my pants down to pee after being pulled from the rubble, chunks of concrete fell out of my underwear, making me hysterical as I tried to conceive where it was all coming from. My teenaged friend Judeline, whose leg was amputated below the knee because of her injuries, says wonderingly, laughing, “Frijolito killed so many people!” Frijolito is the name of the lisping little boy in the Mexican telenovela that everyone was following this time last year. It came on at 5 pm, which is why, according to Judeline, so many people were – unluckily — indoors when the earthquake hit.

Some jokes make their rounds through text messages. As news of cholera broke and the messages about handwashing and water treatment began to spread and enter the popular lexicon, this joke began to circulate via SMS, relying equally on the listener’s familiarity with ubiquitous public health warnings and on the absurdity of that familiar advice when twisted and applied to a piece of equipment:

You can get cholera from your cell phone! To prevent this, scrub your phone well with soap and rinse it with water. If possible, let it soak in a bucket of treated water for at least one hour. If you can’t hear anything after that, give it oral rehydration until it recovers. If it won’t turn on, bury it so that it doesn’t contaminate other phones.

Still another joke plays upon the fact that recent events in Haitian history, when condensed to a list, seem to take on biblical proportions. The particular calamities and the order in which they are listed depend on the speaker (I heard it first from a friend who lost her mother on January 12) but they are always a combination of political events, diseases, and so-called “natural” disasters (which are never entirely natural), and the punch line always remains the same:

Haiti has had nine plagues. The first was AIDS. The second was a coup d’état. The third was Préval. The fourth was another coup d’état. The fifth and sixth were hurricanes Jeanne and Gustav. The seventh was the goudougoudou. The eighth was hurricane Tomas. The ninth was cholera. If you don’t want the tenth plague, don’t vote for Célestin.

Jokes allow people to talk about topics that may be dangerous (politically or psychically or sometimes literally) to discuss directly. Imagining the earthquake as a competition between Jesus and Satan is a way for people, many of whom would never question God directly, to do so obliquely. Leavening stories of earthquake survival with these recognizable moments of humor (the sight of naked neighbors with their hands clasped strategically while the known world collapses, the idea that the cute kid from the telenovela is responsible for the mortality rate) brings the strangeness of the catastrophe back to earth and to reality. Talking about the perils of living under a tarp using Bouki and Ti Malis illustrates vulnerability without naming it aloud; it recognizes and shines a light on the precariousness of the lives of people who not only have to live in tents, but run the risk of losing even that minimal shelter (to thieves or, more likely, to poorly-planned state-sponsored relocation). The joke equating a Célestin presidency to a tenth and final plague is the most dangerous – at once an indictment and warning that Préval’s chosen candidate, Jude Célestin, could be the final straw that breaks this country that has already endured so many unthinkable things.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Not all jokes are political or laden with subtext or half-articulated truths. Sometimes the joke is a form of release from a world that threatens to become unbearable.

The youth writing group I work with meets every Saturday in Pont Rouge, not far from Cité Soleil, where many of the participants live. This past Saturday an American journalist (who, I will add, was kind and patient and seemed to have great integrity) joined us. Marlène , who coordinates the group with me, told this journalist, “If there’s one thing wrong with this group, it’s that they laugh too much, they tell too many jokes.” I can’t disagree — our meetings always start with jokes and teasing, and, if we’re not disciplined, remain irreverent throughout. Normally the writing group is lively and talkative, with plenty of teasing and good-natured argument. We’ve had visitors before, and our group has always welcomed the chance to share their voices with others. In fact, that’s the objective of the group – to share the creativity, potential, and energy of these young people from some of Port-au-Prince’s most stigmatized communities with the larger world. But this Saturday, the participants were withdrawn and reticent. As they say in Creole, they were “lwenn” – far away and thinking of other things.

Then four of the participants performed a text they had written. It began with Assephie out in the hall, narrating in voice-over how full of promise and beauty everything felt at the beginning of January 2010 – a new year in a troubled country that was more stable and calm than it had been in years. Then Andy, on a drum, pounded out the sound of the goudougoudou, and the other performers collapsed to the ground. Marlène began to sing in low, despairing tones, while Assephie emerged, clad in the Haitian flag, her hair in a blue and red kerchief, and then fell to the floor, rocking and wailing.

“Haiti, why are you crying like that? Why are you so sad?” asked Elie, representing the international community.

“How can you tell me not to cry?” demanded Assephie, representing a furious and wounded Haiti. “How can you tell me not to scream, when I think of all my children dead, when I think of everyone taken before they should have gone?”

As the drumbeats rose and fell, some people began wiping away their tears. A couple of the workshop participants, who had lost family in the earthquake, were so shaken that they went into the next room to sob and be consoled. The performance concluded with the other actors lifting up Haiti, saying that they will survive, “put their shoulders together” to sustain themselves, as one says in Creole.

People clapped, and said the piece was beautiful. Then we had to pause because so many people were upset. When things at last calmed down and the group, somewhat dispirited, reconvened, the jokes began. Dénold, who prefers to go by his “artist name” G.Love, got up and addressed the two young women who had been particularly affected by the presentation. “This is especially for you,” he said, and, to cheer them up, as the journalist’s tape continued to record, led the group in a lighthearted call-and-answer poem extolling the virtues of women. Then Elie stood and confidently prefaced, “once you hear this, you won’t be able to stop laughing.” Expecting people’s spirit to be low, he had been saving his piece until after the presentation, and offered it as a kind of a conciliatory gesture. He began to recite a poem of his own devising, which seemed to be a sopping, syrupy love poem, only to reveal in its final line that it was not about his love for a girl but about his love for lam bouyi – boiled breadfruit. And then (why not? It’s not every day you find yourself on Public Radio International) I told a joke that concerns a young man, eager to make a good impression on his new girlfriend’s family, wrongly thinking he’s gotten away with blaming his farts on the dog. By now people were laughing out loud, wiping away tears again.

It felt awkward but true. The journalist had wanted to hear the voices of underrepresented young Haitians, and, this week, a few days before douz janvye, those were their voices: muted, trembling, sad, and joking. It wasn’t exactly a redemptive story. The fact that they were laughing is not necessarily inspirational, hopeful, or soothing. It does not allow us to say, “You see, they’ve still got laughter. Everything is going to be all right in Haiti.”

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Everything is obviously not all right in Haiti. It is very far from all right. It is facile to assume that laughter is necessarily an expression of happiness. In the words of Haitian novelist Jacques Stephen Alexis, in General Sun, My Brother: “We blacks joke all the time. When we are suffering, we laugh and make jokes. When we are dying, that is, when we have finished suffering, we laugh, sing, and make jokes.”

Joking can be a way to cope. Joking can be the telling of uncomfortable or hard-to-articulate truths. Joking allows one to assert one’s humanity in what would seem to be impossibly dehumanizing conditions – of saying that despite everything, the speaker is still here, still a person, and still telling a story rather than being dissolved and absorbed into the story. Joking can be an act of defiance and fury, a way of shaking your fist in the face of injustice, of momentarily wresting control from a world that threatens to bend and vanquish you. It is speaking truth to power – a way to laugh at earthquakes, to laugh at politics, to laugh at cholera, to laugh at God, to laugh at death.